| Author Name | YODO Masato (Kyoto University) / YANO Makoto (Chief Research Officer, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

1. Background

Social capital is a concept that refers to the norms of trust and reciprocity between people and their networks, and each person has his or her social capital. In pre-modern societies, where bonds with other people—whether by a shared locality or blood—played an important role in daily lives and various economic activities, people had a clear incentive to build social capital. However, in today's market-oriented society, where bonds by a shared locality and/or blood play a far less important role, what incentives do people have to build social capital?

Since social capital concerns how people relate with other people, studies on it have tended to focus on its externalities as compared to those on human capital. However, even if social capital generates externalities, would people have any incentive to build it without any benefit to themselves?

Driven by these questions, this study aims to investigate the impacts that the formation of social capital has on people's income (Note 1) as an economic outcome; whether individuals can work to build social capital intentionally given an incentive in the form of an expected increase in income; and what they can do to build social capital.

2. Methods used in analysis

Although many studies have attempted to examine the relationship between social capital and economic outcomes, very few have properly taken into consideration the causality between them. The causality runs both ways, and, if we disregard that fact, we cannot estimate the impact of social capital accurately. For the purpose of this article, we have employed the instrumental variable estimation method to address this problem.

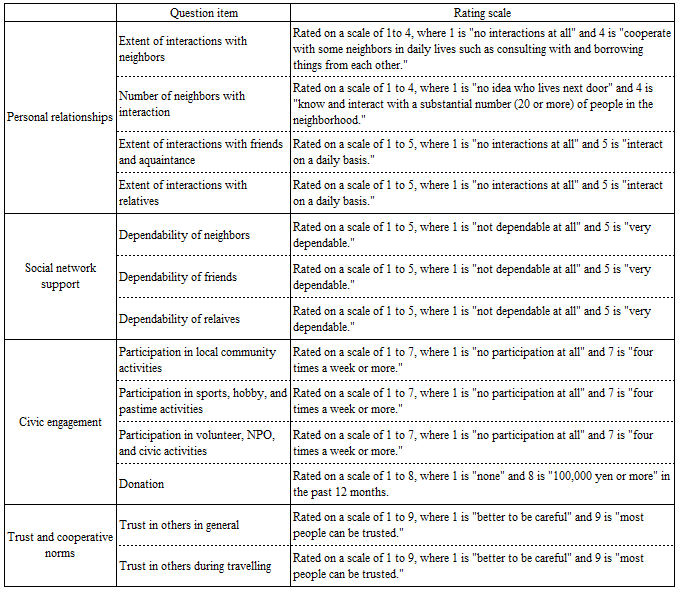

Meanwhile, in order to consider various aspects of social capital, we have developed four indices corresponding to the four types of social capital proposed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): 1) personal relationships, 2) social network support, 3) civic engagement, and 4) trust and cooperative norms. Using them, we attempted to clarify the relationship between various aspects of social capital and income.

For this analysis, we used data from a nationwide survey conducted by Yoji Inaba of Nihon University in 2010 and 2013 on the sense of tranquility in life, trust, and community participation (Note 2). The questionnaire for the survey consists mainly of questions concerning social capital but also includes those on health and everyday life. The survey received 1,599 effective responses in 2010 and 3,575 in 2013. We selected 13 questions concerning social capital, classified them into the four groups as defined by the OECD, and developed the corresponding indices by applying the principal component analysis (PCA) method (Note 3).

In establishing causality between a dependent variable and an endogenous explanatory variable by using the instrumental variable method, it is necessary to find another variable correlated with the endogenous explanatory variable but not with the error term in the equation for estimating the explanatory variable, and use it as an instrumental variable. In this study, we use the degree to which respondents find their relatives dependable as an instrumental variable for social capital, and the degree to which respondents worry about their future income (Note 4). As for the first instrumental variable, i.e., the dependability of relatives, the relationship with relatives may lead to some sort of economic benefit. Thus, in order to address this possibility, we have also conducted analysis by limiting our sample to those living in populous urban areas where personal connections such as blood kinship are unlikely to affect economic activities.

3. Conclusion and insights

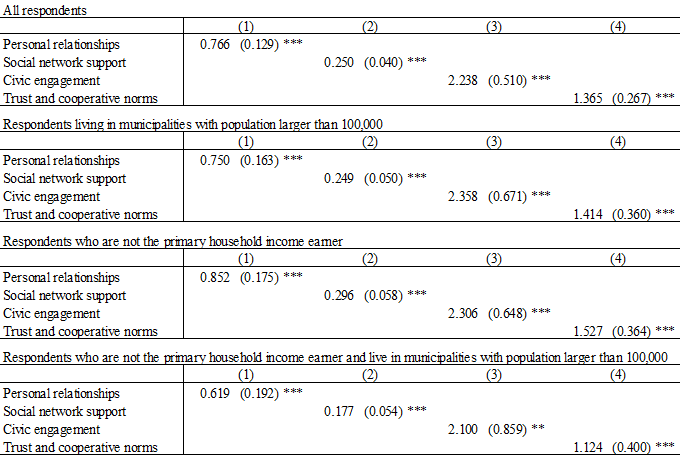

Our analysis found that social capital and income have positive effects on each other. This holds true for all of the four aspects of social capital. Furthermore, we found that social capital contributes positively to income even when we limit the sample to those living in urban municipalities defined as those having an above-threshold population (Table 2). The positive causality from social capital to income is also observable when we limit the sample to those who are not the primary household income earner. In other words, even when possessed by non-primary earners, social capital contributes positively to overall household income. This suggests the possibility that social capital generates externalities even within a household, the minimum unit of society.

Note 2: Standard errors are shown in parentheses.

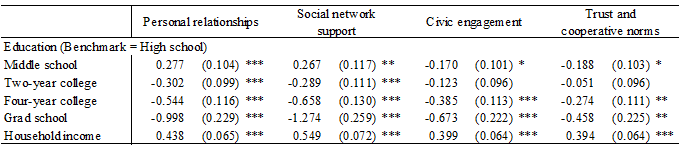

Furthermore, our analysis of factors affecting social capital formation found that college education contributes positively to the formation of social capital. When the endogeneity of income is taken into account and controlled for, the completion of high school education has a significantly positive impact on two types of social capital, i.e., "civic engagement" and "trust and cooperative norms," but contributes negatively to the other two, i.e., "personal relationships" and "social network support" (Note 5). Meanwhile, a technical or two-year college level education contributes negatively to "personal relationships" and "social network support," whereas education at a four-year college or higher level contributes negatively to all of the four aspects of social capital (Table 3). This indicates the possibility that education per se may have a negative direct effect on social capital, that is, when income is constant. However, a higher level of education contributes positively to income, and higher income contributes positively to social capital. The indirect effect through this channel is particularly large for four-year-college education, resulting in a net positive effect on the formation of social capital (Note 6).

The above findings indicate that individuals may be able to increase income by proactively building their social capital. Although the formation of individual social capital is influenced by various factors unrelated to individuals' intent, they can proactively build their social capital by means of education. In other words, individuals can be incentivized to build social capital even in today's market-oriented society. This suggests that it is possible to facilitate the formation of social capital by working on incentives and hence points to the importance of developing government policies toward that end.

Note 2: Standard errors are shown in parentheses. *, **, *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively.

- Footnote(s)

-

- ^ For the purpose of this analysis, we use annual household income due partly to constraint on data availability but also because the use of household income enables us to analyze the impact of social capital possessed by an individual on his or her household.

- ^ The 2010 survey was conducted as part of a research project led by Yoji Inaba and supported by Nihon University Research Grant for FY2010 to study age-friendly city planning in consideration of social capital. The 2013 survey was conducted as part of "Policy Implications of Social Capital," a research project (No. 24243040) led by Yoji Inaba and funded by the government's Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) program. We would like to thank Professor Yoji Inaba of Nihon University's College of Law for permitting the use of data for our study.

- ^ Principal component analysis (PCA) is a method to extract the principal component from a set of multiple indicators in such a way as that the component contains as much information as possible contained in the original set. For instance, it is possible to develop a comprehensive indicator measuring the degree of association from a set of three indicators measuring the degree of association with neighbors, relatives, and friends respectively.

- ^ Considering the effects of intertemporal dynamic optimization, it is highly probable that individuals determine the degree to which they accumulate social capital at the present level by taking into account their future prospects. Therefore, people's anxiety about the future and their present income must have something to do with each other. We could apply the same thinking to social capital. However, it is not realistic to assume that people's anxiety about the future determines how they trust in and associate with others today.

- ^ Among the respondents sampled for this study, those who did not complete high school education are mostly elderly. Presumably, many of those elderly respondents were unable to receive adequate education due to economic difficulties, and this might have affected our findings. This is one of the issues left for further consideration.

- ^ We can confirm that four-year college education has a net positive effect on the formation of social capital by estimating a reduced form from the equation for income and the equation for social capital. The net effect of high school education on the formation of social capital, which factors in its indirect effect, is not negative because completing high school education contributes positively to income.