There is concern about the persistent slowdown of economic growth in the aftermath of financial crises. This column argues that excessive debt, which was accumulated in firms and households as a result of financial crises, can cause persistent stagnation. The continued weakness observed in the developed economies may not be due to exogenous technological shocks, but due to excessive debt. A noticeable implication is that relief from excessive debt may restore economic growth directly, whereas unconventional monetary and fiscal policies proposed and implemented in the last several years might be useful for buying time, but not for directly solving the fundamental debt problem.

The long-lasting effects of a financial crisis on the real economy are a puzzle, as the crisis by nature is a short-run event. As Kozlowski, Veldkamp, and Venkateswaran (2016) argue, the existing explanations assume that the shocks that trigger a persistent recession are continuous. Kozlowski et al. give another explanation that a one-time crisis changes people's expectations of tail risks indefinitely. In this column, we focus on another persistent change in the real economy due to short-run financial crises, which is the accumulation of huge amounts of excessive debt in firms and households. We argue in what follows that a one-time buildup of excessive debt can depress the economy interminably even if there is no change in financial technology, based on our theoretical study (Kobayashi and Shirai 2017).

Whether or not the buildup of debt can cause a persistent recession is of practical importance when we assess policy recommendations. If persistent stagnation is due to exogenous technological shocks (e.g., Gertler and Kiyotaki 2010, Christiano, Eichenbaum and Trabandt 2015) or an unwavering change in expectations of tail risks (Kozlowski et al. 2015), policymakers can mitigate a recession simply by accommodative monetary and fiscal policies, because they can do nothing directly to eliminate exogenous shocks or expectations of tail risks. If, on the contrary, a recession is due to accumulation of excessive debt, they can cure it by simply reducing debt. Debt reduction is not necessarily the liquidation of overly indebted borrowers, but may be just their relief from debt by debt forgiveness or debt-for-equity conversions. Even in this case, unconventional monetary and fiscal policies may be effective to mitigate the severity of recessions, whereas their ultimate function is to buy time and not to cure the recession itself. At the least, we can say that if excessive debt is the problem behind a persistent stagnation, it may be necessary to expand choices for policymakers. Choosing among monetary easing, fiscal policy, and ex ante macro-prudential regulations may not be a satisfactory framework for policy debate, but we may need to explicitly compare them with ex post policy measures to accelerate debt reduction in the private sector.

Why does excessive debt cause persistent stagnation?

Our model is an economy where an excessive amount of inter-temporal debt works as debt overhang that tightens the borrowing constraint for working capital, i.e., intra-temporal debt. Debt overhang (Myers 1977) has not been considered as an issue of macroeconomic policy because it is usually resolved quickly through the bankruptcy process in the firm level. Lamont (1995) shows that debt overhang can cause a recession when it exerts externality, but it should be short-lived and the problem would resolve itself fairly quickly. In our model, debt overhang is potentially permanent in the firm level, and can cause a persistent recession in the aggregate level, which can be interpreted as "secular stagnation."

Our model is similar to Jermann and Quadrini's (2012) theory, whereas our deviation is that the lender can seize a portion of output unilaterally from the defaulted borrower before starting renegotiation in the bankruptcy procedures. This difference enables the lender to make working capital loans to the borrower even when he or she already holds the maximum amount of debt. The banks are willing to lend working capital, albeit small, to debt-ridden firms, because the loans are secured by their ability to seize unconditionally a portion of output when the borrowers default. In Jermann and Quadrini's model, the borrower who owes the maximum amount of debt cannot borrow working capital, thus, it stops production and exits the market immediately. In this way, inefficiency of debt overhang disappears quickly in their model, while it may continue indefinitely in our model. This is because firms with maximum debt can continue production, although inefficiently, by borrowing a small amount of working capital. We call such a firm debt-ridden.

A large number of debt-ridden borrowers emerge as a result of a financial crisis. This is because a financial crisis is typically associated with plummeting asset prices in real estate and stock markets. These assets have been used as collateral to secure debt, and the plummeting prices make a substantial part of the debt unsecured, which works as debt overhang. The emergence of a huge number of debt-ridden firms may lower productivity growth in the aggregate level, as the tightened borrowing constraints depress research and development (R&D) activities by the firms.

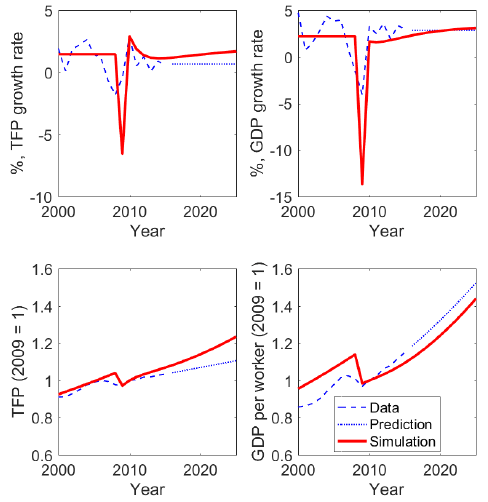

Our model can replicate the levels and the growth rates of gross domestic product (GDP) and total factor productivity (TFP) of the United States, as we see in the Figure. In this numerical experiment, we assume that 60.7% of firms became debt-ridden suddenly and unexpectedly in 2009. This figure shows that the buildup of excessive debt can account fairly well for the persistent economic slowdown in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Debt reduction as a macroeconomic policy

Under the long-lasting ineffectiveness of monetary policy, Sims (2016) proposed another unconventional monetary-fiscal policy, which is to use deficit financing of government spending as a tool for pushing up the price level. One factor that brought about the ineffectiveness of monetary policy should be the persistent weakness in the real economy after the financial crisis. Our study indicates that relief from excessive debt for the debt-ridden borrowers can strengthen the real economy, which then can restore an environment where conventional monetary policy works well. Eventually, reducing excessive debt could make unconventional monetary policy unnecessary. This line of thought may lead to a notion that debt reduction after a financial crisis can work as a macroeconomic policy that restores economic growth. Debt reduction here does not necessarily means physical liquidation of debt-ridden firms. Our model implies that relief of debt-ridden borrowers from excessive debt can improve their own efficiency, resulting in the aggregate productivity of the economy as a whole.

Our theory implies that when the borrowers are debt-ridden, the banks have no incentive to forgive excessive debt burdens. This is because they can be satisfied with the repayment from debt-ridden borrowers, even though the borrowers themselves suffer from inefficiency due to debt overhang, which in turn depresses the aggregate economy. In the "laissez-faire" environment, the debt-ridden firms stay in the market once they emerge, and the aggregate inefficiency continues persistently. Thus, the excessive debt does not resolve itself in the market, implying that the wait-and-see strategy of the government, which essentially is just buying time using unconventional monetary and fiscal policies, does not work. Active interventions by the government therefore must be necessary to restore economic growth in a timely manner by promoting debt restructuring or wealth redistribution from lenders to borrowers. Policy measures may include regulatory reforms to make bankruptcy procedures less costly and more debtor-friendly and to promote debt-for-equity conversions to reduce outstanding debt, and the injection of subsidy (or equity) to the banks that forgive debt and write off nonperforming loans. The injection of bank subsidy or equity is usually interpreted as bank recapitalization, because the banks become insolvent in most cases when a substantial number of their borrowers fall into debt-ridden status. This policy implication is straightforward and seems reasonable from our experience of recent financial crises in Japan (1990s) and the United States and Europe (2008 and on), whereas existing theories may not clearly imply that borrowers' relief from excessive debt is good for a crisis-hit economy.