This article introduces recent academic findings on the effects of export promotion policies. Export promotion policies for the purpose of discussion here refer to those implemented by public export promotion agencies (EPAs) in the form of direct support to exporting firms, excluding subsidization of production and investment, which could be export promotion measures defined in a broad sense. Specific types of support include: offering information on destination countries and export procedures, assisting firms' participation in overseas market survey missions and trade fairs, and supporting firms with their negotiations with importing firms. Agencies providing such support are in place in at least 103 countries as of 2005 (Lederman, Olarreaga, and Payton, 2010). In Japan, a series of government-affiliated agencies such as the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), and the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) provide support to exporting firms.

Theoretical framework

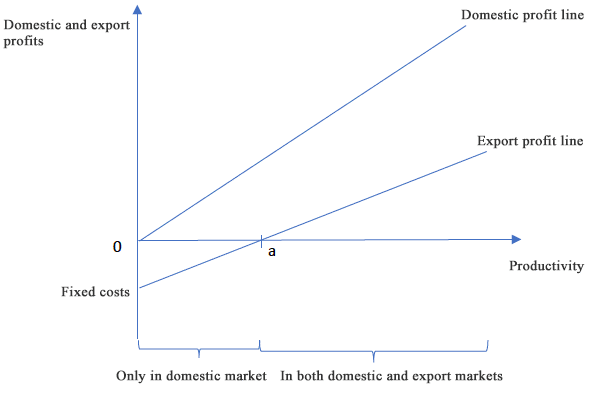

The Melitz model (Melitz, 2003) has often been used in the recent international trade theories. Using the model, I explain the mechanism through which export promotion policies affect firms' export behavior. Figure 1 shows the relationship between profits (in domestic and foreign markets, respectively) and firm productivity. The horizontal axis measures the firm productivity and the vertical axis measures firm domestic and export profits. For the sake of simplicity, the fixed cost of domestic production is ignored here. Accordingly, the domestic profit line can be drawn as an upward sloping line starting from the origin, i.e., the higher the productivity, the greater the profit.

How does the export profit line look? The Melitz model assumes that exporting involves two types of costs: variable costs that are incurred in proportion to the quantity of exports and fixed costs that are incurred regardless of the quantity of exports. The former includes transportation costs such as the cost of sending products by air freight as well as tariffs, while the latter includes initial costs such as costs involved in customs clearance procedures and costs incurred while finding and signing contracts with distributors in destination countries. Because of the latter, the export profit line starts from a negative value equal to the total fixed cost of exports. The variable costs of exports, on the other hand, make the slope of the export profit line lower than that of domestic profits, because firms with higher productivity export more products. As a result of these costs, firms with lower productivity (those whose productivity is below a in Figure 1) operate only in their domestic market, whereas firms with higher productivity (those with productivity above a in Figure 1) operate in both domestic and export markets.

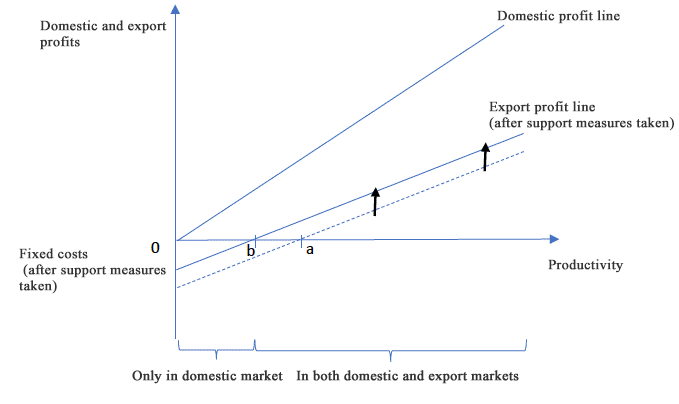

Under the situation, how would export promotion policies operate? If a support measure has the effect of lowering fixed costs such as costs involved in the initial customs clearance procedures and those incurred for finding and negotiating with distributors in export destinations, it will increase export profits for all firms, hence, the entire export profit line will move up. In contrast, if the support measure has the effect of lowering variable costs, for instance, in the form of a decrease in transportation costs, it will increase the slope of the export profit line with its y-intercept kept unchanged. The former case is plotted in Figure 2. It shows that the former type of export promotion measures motivates relatively highly productive non-exporting firms, those whose productivity falls between b and a, to enter the export market. This simple model with firm heterogeneity in terms of productivity suggests that export promotion measures are effective in motivating firms with medium-level productivity to enter the export market.

In reality, firms are heterogeneous in many aspects other than productivity. For instance, even when two firms are the same in productivity, fixed costs incurred by one firm in searching for an export distributor may be smaller than those incurred by the other because the former happens to have contacts in its export destination. Likewise, if one firm's products have greater demand in export destinations than those of the other, the former outperforms the latter in export profits even when they are homogeneous in both productivity and fixed cost of exports. Such differences in fixed costs and demand are important factors explaining firms' export patterns (Eaton, Kortum, and Kramarz, 2012). In terms of how these additional factors are related to export promotion policies, the presence of information barriers is quite important. Information barriers and the roles of promotion policies against them have been highlighted in recent literature (Volpe Marticus, 2010). Based on this idea, export promotion policies should have a particularly significant impact on those firms faced with large barriers to information access such as: 1) small firms, 2) firms exporting differentiated products, and 3) firms attempting to export for the first time.

In summary, implications of the theoretical model are as follows:

- Export promotion policies motivate firms, particularly those with medium-level productivity, to enter the export market by lowering costs of exports.

- Barriers to information access are significant as a fixed cost factor, and export promotion policies alleviate them.

- Export promotion policies have a particularly significant impact on small firms, firms exporting differentiated products, and firms attempting to enter the export market.

Empirical studies

Empirical studies on export promotion policies can be classified into two broad categories depending on the type of data used. Those in the first category use country- and/or regional-level data on exports, combined with data on funding allocated to export promotion policies or information collected through overseas EPA offices. Those in the second category use firm-level data on export behavior and on the use of export support services. In what follows, I will focus my discussion on the identification problem regarding the effects of export promotion measures and the approaches used to address this problem. The identification problem here concerns how to identify the causal effects of export promotion measures on firm performance. For instance, a positive correlation between a firm's use of an export promotion measure and the value of its exports may be reflecting the causal effect of the export promotion policy on exports, or it may simply be the consequence of reverse causality, i.e., firms willing to export are apt to take advantage of export promotion support (self-selection bias). Typical approaches to addressing the identification problem in empirical analysis of export promotion policies include an instrumental variables estimation, a difference-in-differences estimation, propensity score matching, estimation using a sub-sample in which self-selection bias is limited, and controlling for fixed effects or numerous variables. For a more comprehensive survey, see Van Biesebroeck, Konings, and Volpe Marticus (2016).

Country- and regional-level data:

The first step in analyzing the effects of export promotion policies is to conduct studies using country- and/or regional-level data, which are relatively easy to access. However, these studies often have different results depending on their target and the estimation method used. For instance, Lederman, Olarreage, and Payton (2012) examine the impact of the amount of the EPA funds on the value of exports, using cross-sectional data on exports and EPA funding across countries. Because the EPA funding is considered as an endogenous variable, which is influenced by the value of exports, they estimate the causality using the following two instrumental variables: 1) the number of years to the next election, and 2) the number of years since the establishment of the EPA. According to their findings, a 1% increase in the EPA funding increases the value of exports by 0.06% to 0.1%. On the other hand, Bernard and Jensen (2004) analyze the effects of export promotion expenditures by state governments in the United States on the export behavior of firms located in the respective states. Because state expenditures on export promotion are presumably affected by the export behavior of firms located within the state, they use a model including a series of observable state- and firm-level variables to be controlled for. By controlling for these variables, they assume that state expenditures on export promotion would be determined randomly. Under this framework, they find that state expenditures on export promotion have no noticeable effects on firm export behavior (Note 1).

Lastly, Hayakawa, Lee, and Park (2014) analyze how the local presence of EPAs—i.e., overseas offices of the JETRO and those of the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA)—in countries around the world affects the value of Japanese and South Korean exports to those countries. As is the case with the above-cited studies, they consider the possibility of reverse causality, that is, the value of exports to a specific country may be affecting the decision to set up an EPA office in that country. In order to address this problem, they use importer-year and exporter-year fixed effects to control for time-varying factors in exporting and importing countries. They find that the establishment of an EPA office in an export destination (importing country) boosts the value of exports to that country by 61% to 66%. As such, despite numerous attempts to estimate causality using various approaches and datasets, studies based on country- and/or region-level data have so far not produced any conclusive results.

Firm-level data:

Average effects:

Recent literature analyzing the effects of export promotion policies includes a multitude of studies that have found a positive effect of export promotion policies on firms' export behavior using firm-level data in each country (Munch and Schaur, 2018 for Denmark; Broocks and Van Biesebroeck, 2017 for Belgium; Van Biesebroeck, Yu, and Chen, 2015 for Canada; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010a for Uruguay; Volpe Martincus, Carballo, and Garcia, 2012 for Argentina; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2008 for Peru; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010b for Chile; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010c; 2010d for Costa Rica). In addition to research using existing data on export promotion policies, there are also several studies that use randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to examine the effectiveness of interventions. One of them is Kim, Todo, Shimamoto, and Matous (2016), which conduct an RCT on an export support measure in Vietnam and find that the measure had a positive effect on medium-sized firms in terms of encouraging them to enter the export market (Note 2).

Let's take a specific look at some of the studies with observational data cited above. Munch and Schaur (2018) analyze the effects of export promotion policies on firms' export behavior, export values, profits, labor productivity, etc., using data on export support services provided by the Denmark Trade Council. In order to capture the causal effect of export promotion measures on firms' behavior, they select a control group of firms comparable to those that receive support services by using the propensity score matching and then analyze the differences between the two groups in performance changes over time in a difference-in-differences approach. In addition, they examine the effect of export support services on those firms that are approached by the Trade Council, a subgroup of the treatment group. This analysis is premised on the following assumption: Trade Council officials select firms to approach based on observable firm characteristics (which are also observable to econometricians)—e.g., selecting firms belonging to industries that are showing significant growth in local markets overseas—and thus, those firms' participation in the support program is considered random once such observable variables are controlled for. As a result of this analysis, they find that: 1) export support services increase the probability of firms being exporters in the year they receive such services by an average 3.9 percentage points, and 2) the probability increases by 5.9 percentage points two years after receiving such services.

Broocks and Van Biesebroeck (2017) analyze the effects of export support services on Belgian firms' exports to countries outside the European Union (EU), using data provided by Flanders Investment and Trade (FIT), a Belgian EPA. In analyzing the causality between export support services and firms' export behavior, they control for observable characteristics of firms. Furthermore, in order to check the robustness of the results, they perform the same analysis by restricting the sample to firms with 20 or more employees. This additional analysis is based on the presumption that self-selection bias is relatively small in this subsample of firms because, in a small economy like Belgium, advancing into foreign markets is vital for firms above a certain size. As a result, they find that export support services increase the probability of exporting by an average of 8.5 percentage points. As such, empirical studies using firm-level data generally find a positive effect of export promotion measures.

Effects by firm characteristics:

What has been discussed above is about the average effects of export promotion policies. However, those measures should have different effects on individual firms depending on their characteristics. Indeed, many studies have actually shown some differences in the pattern of effects depending on firm characteristics. For instance, regarding the effects of export promotion measures by firm size, some studies show that export promotion measures have a particularly strong positive effect on small firms (Munch and Schaur, 2018; Broocks and van Biesebroeck, 2017; Volpe Martincus, Carballo, and Garcia, 2012; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010b), whereas some other studies find a particularly positive effect on medium-sized firms (Olarreage, Sperlich, and Trachsel, 2015; Kim, Todo, Shimamoto, and Matous 2016). There are also those studies that examine the relationship between product types and the effectiveness of export promotion policies, with the conclusion that the measures are particularly effective on firms exporting complex and differentiated products (Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010a; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010b). It has been also shown that export promotion measures have a greater impact on firms entering the export market for the first time or attempting to expand into new markets, than on those that are already established as regular exporters (Munch and Schaur, 2018; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010a; Volpe Martincus, Carballo, and Gallo, 2011; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2008; Volpe Martincus and Carballo, 2010c). These findings are consistent with hypotheses represented by various theoretical models, particularly one that considers barriers to information access as an obstacle to entering the export market.

Effects by type of support:

As described above, there exist many studies that have examined the effects of export promotion policies, but very few have gone so far as to analyze the effects characterized by the types of support given to firms. Volpe Martincus and Carballo (2010d), Broocksand Van Biesebroeck (2017), and Munch and Schaur (2018) are among the very few examples of such studies. Volpe Marticus and Carballo (2010d) analyze the effects of different forms of export promotion, using panel data provided by Proexport Colombia. Specifically, they group export promotion measures into 1) "counselling" which includes providing information on export destinations and training in export procedures, 2) "trade agendas" which refers to assisting with arrangements for business meetings and negotiations, 3) "trade fairs, shows and missions" which provides support for firms participating in trade fairs, shows, and missions, and combinations of those, and compared their effects. The problem here is distinguishing between two possible relationships. That is, when a certain firm succeeds in exporting goods, is it because the firm has taken advantage of type A support (e.g., trade fairs, shows and missions), or is it simply due to the fact that firms likely to succeed in exporting goods are apt to choose to take advantage of type A support? In order to address this identification problem, they select a control group of firms similar to those in the treatment group by using propensity score matching, and then analyze the differences between the two groups' performance changes over time in a difference-in-differences approach. They find that firms supported by all types of export promotion programs in a bundle show more pronounced growth in terms of the total value of exports and the number of export markets than those supported by individual programs.

Broocks and Van Biesebroeck (2017), which I introduced above, conduct an additional analysis in which they compare the effectiveness of different types of export promotion services, restricting the sample to those firms supported by such services. They classify services into "questions" in which firms make inquiries about matters requiring information analysis, etc., "actions" which refers to events and seminars, "subsidies" which assist firms in making business trips, participating in trade fairs, arranging meetings with distributors (by subsidizing costs incurred), and "communication" which includes those services that do not fall into any of the above. According to their findings, firms that receive "subsidy" support achieve a 4.6- to 8.4-percentage-point higher probability of exporting than those that receive "question" and "communication" support. Lastly, Munch and Schaur (2018) classify support services used by firms into two types, "partner search and matchmaking" and "intelligence and analysis," to examine respective effects of each type of support services, as an additional analysis to the above-discussed average effects. According to their findings, small firms' probability of exporting increases by 9.4 percentage points two years after receiving the former type of support services, and by 6.7 percentage points in the case of the latter.

The findings from the analysis by type of support services suggest that bundled services combining multiple types of support—and more direct measures such as helping firms find distributors from the individual support services—are more effective.

Concluding remarks

This article reviews and organizes theoretical and empirical studies published in recent years in the field of international economics in terms of how they analyze the effects of export promotion policies. Using firm-level data, a series of empirical studies have shown the effectiveness of export promotion policies. However, it goes without saying that further analysis is needed. It is necessary to analyze the precise effects of export promotion measures, for instance, what types of measures are effective for what types of firms. Also, it would be useful to analyze not only effects on firms that receive support but also spillover effects on those that do not. Furthermore, studies using RCTs to address the problem of self-selection into export promotion measures or those in which estimation is made under weak assumptions, thereby allowing for self-selection, would be useful for checking the validity of the findings (Note 3).

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank RIETI Vice President Masayuki Morikawa and Fellow Shota Araki for their very helpful comments.

The original text in Japanese was posted on November 16, 2018.