| Author Name | HASHIMOTO Yuki (Fellow (Policy Economist), RIETI) / Takahashi Kohei (Waseda University) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Comprehensive Research on Evidence Based Policy Making (EBPM) |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Policy Assessment (FY2020-2023)

Comprehensive Research on Evidence Based Policy Making (EBPM)

Higher labor productivity at small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is crucial for further economic growth in the context of population decline, and was a focus of the 2020 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan. However, many SMEs are making little progress in raising labor productivity since 2000s. This is especially true of firms that cannot make the capital investments required due to factors such as funding constraints. Against this background, the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency established the Business Sustainable Subsidy (BSS) in 2013 to boost SME market development and labor productivity. In this paper, we examine the impact of application and receipt of the BSS on small enterprises' sales and productivity.

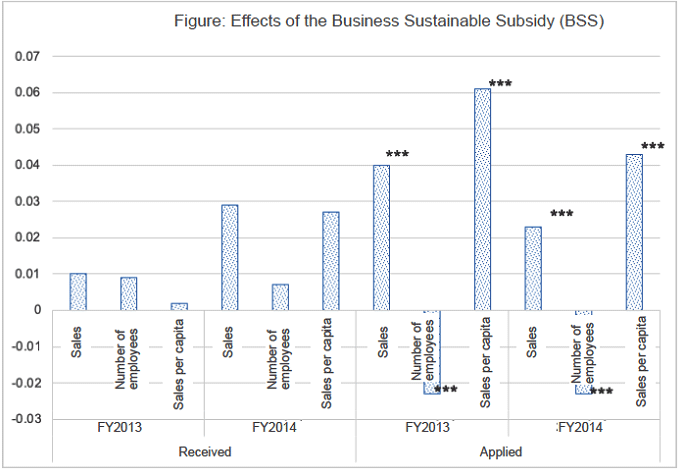

We analyze data by combining a list of all the firms that applied for the BSS in FY2013 and FY2014, and firm data compiled by Tokyo Shoko Research (TSR). We assess the effects of the subsidy by examining changes in sales, number of employees, and sales per capita before and after an application for the subsidy was made and received, for firms that applied for and received the subsidy, and comparing these with firms that did not.

Several opportunities are provided for firms to apply for the BSS each year, and a separate cutoff point for receiving the subsidy is established each time. We therefore employ a sharp regression discontinuity design (sharp RDD) to estimate the effects of receiving the subsidy, and confirm the robustness of our findings through a difference in differences (DID) analysis. Regardless of the analytical method, we did not observe a significant increase in outcomes such as sales as a result of firms receiving the subsidy.

However, prospective applicants for the BSS are required to prepare a business plan with support from management advisors from the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (JCCI) or the Central Federation of Societies of Commerce and Industry (CFSCIJ). The application process therefore gives firms the opportunity to identify the issues they face and examine their future business outlook. This mechanism may effectively enhance the business performance of subsidy applicants, even if they are not actually selected to receive the BSS.

To estimate the effect of applying for the BSS, we therefore employ DID analysis of a data sample that includes firms that did not apply for the subsidy. The figure below shows the results of our estimation based on application and receipt of the BSS, respectively. For firms that applied for the BSS, while we observe a significant increase in sales after the application, when compared with firms that did not apply, there was a significant decline in the number of employees. We also observe a significant positive correlation with sales per capita, which we treat as a productivity indicator. An analysis by industry (for the manufacturing, construction and service industries) indicates that this tendency is particularly apparent in the service industry.

We test the robustness of these results using a placebo analysis, and find that the result for FY2013 is both significant and robust. For FY2014, however, there are indications of possible selection bias, with firms that could be expected to gain the greatest effects from the subsidy more likely to actually submit an application.

To summarize the results of our analysis, although we found no significant difference in outcomes between firms that received the subsidy and those that did not, we did find that productivity improved for firms that applied for the subsidy compared with those that did not. This suggests that the effects were due not to financial support from the subsidy, but rather to the application process itself. Our findings imply that external advice from organizations such as chambers of commerce and the preparation of business plans, which form part of the application process, provide firms with an opportunity to identify and address their issues, effectively improving productivity. It may be that the inclusion of such mechanisms to promote voluntary efforts is an effective design for the implementation of subsidy policies aimed at developing small enterprises.