| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Macroeconomy and Low Birthrate/Aging Population (FY2016-FY2019)

East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances

When risk aversion increases, investors channel capital to safe haven currencies such as the Swiss franc and the Japanese yen. The resulting appreciations can squeeze profit margins if exporters must lower local currency export prices to remain competitive. They may also reduce the volume of exports. How can firms in countries with safe haven currencies weather large appreciations?

Producing differentiated products may help. Producers of commoditized products can face intense price competition, forcing firms to slash domestic currency export prices and compress profit margins when the exchange rate appreciates. Producers of differentiated products may not only be able to reduce domestic currency prices less during appreciations, they may be able to raise these prices more when the exchange rate depreciates.

Ito, Koibuchi, Sato, and Shimizu (2018) introduced a way to measure how differentiated a product is. They showed that, unlike for homogeneous goods, firms exporting differentiated products and firms dominating global markets tend to invoice in the exporter's currency.

Examining the Japanese transportation equipment industry sheds light on this measure. At one extreme is passenger cars, with only 8 percent of exports over the 2000-2015 period invoiced in yen. Nguyen and Sato (2019) noted that cars have become commoditized. At the other extreme is bicycle parts, with 91 percent of exports invoiced in yen. Lewis and Morizono (2016) observed that Japan's Shimano Corporation produces 75 percent of the world's supply of bicycle brakes and gears.

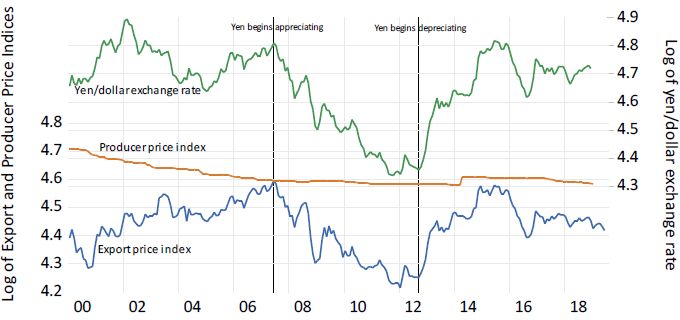

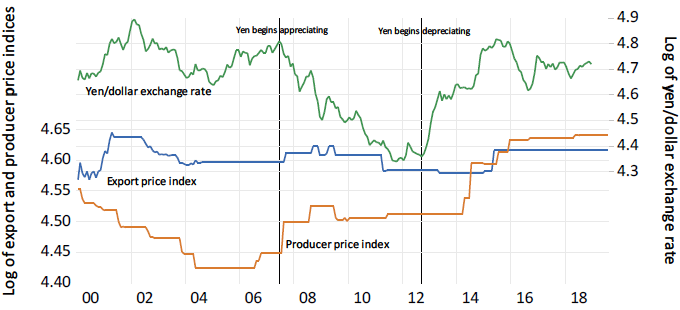

Figures 1a shows the relationship between yen export prices and yen costs for Japanese passenger cars and Figure 1b shows this relationship for Japanese bicycle parts. Figure 1a shows that yen prices for cars fell logarithmically by 40 percent relative to yen costs (represented by the producer price index for passenger cars) after the yen began appreciating in June 2007. Figure 1b on the other hand shows that there was little change in yen export prices for bicycle parts relative to yen costs (represented by the producer price index for bicycle parts) during the yen appreciation period from June 2007 to September 2012.

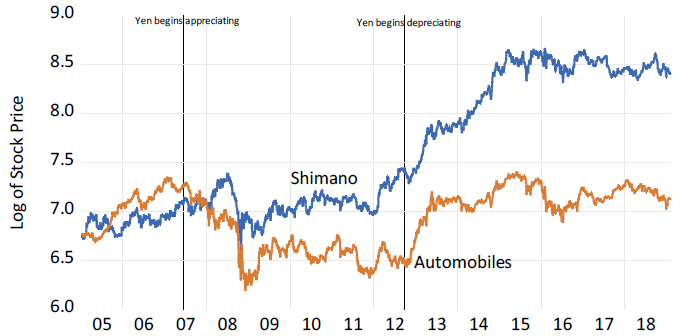

The fact that yen export prices fell so much relative to yen costs for the automobile industry but not for the bicycle parts industry suggests that the profitability of the automobile industry suffered more during the strong yen period from June 2007 to September 2012 than it did for the bicycle parts industry. Stock prices provide one indicator of profitability, since they equal the expected present value of future cash flows. Figure 2 plots stock prices for the Japanese automobile sector and for Shimano Corporation. It shows that stock prices for automobile producers fell almost 90 percent during the strong yen period and only began recovering in September 2012 as the yen depreciated. On the other hand, stock prices for Shimano increased almost 30 percent during the endaka period.

This paper investigates whether Japanese transportation industry exports that are invoiced in yen – where yen invoicing is used to indicate whether the product is more differentiated or commands a larger share of the global market – are less exposed to exchange rate changes. Focusing on the transportation industry rather than on all industries reduces variation across other dimensions that might affect pricing such as the skills and knowhow required to produce a certain good. The paper examines whether long run exchange rate pass-through is larger (and long run pricing-to-market, PTM, smaller) for goods that are invoiced in yen. The results indicate that, the more firms invoice a product in yen, the more they pass-through exchange rate appreciations into foreign prices. This suggests that firms producing differentiated products or firms with larger market shares are better able to maintain profit margins in the face of yen appreciations.

The paper then examines export elasticities for the transportation industry. Sectors such as auto parts and motorcycles that pass-through large shares of yen appreciations also have low exchange rate elasticities. The finding that exports in these sectors are not sensitive to exchange rates implies that firms producing these goods have more freedom to raise foreign currency prices when the exchange rate appreciates.

Finally the paper investigates the exposure of Japanese stocks to exchange rates in the transportation industry. Stock prices are the expected present value of future cash flows, so they should reflect profitability. The results indicate that the firms that pass-through more of their exchange rate changes to export prices, such as makers of commercial vehicles, trucks, and bicycle parts, are also less exposed to exchange rate changes than firms that price to market.

Countries such as Japan and Switzerland could try to keep their currencies weaker to shield their industries from appreciations. However, exogenous sources of risk are likely to arise in the world economy and generate safe haven inflows that will appreciate their currencies. During risk-on periods when their exchange rates are weaker, they should use R&D policy to promote technological upgrading so that firms can develop knowledge-intensive, differentiated products. They should also nurture startups. Finally, they should invest in human capital so that workers can innovate in order to confront the challenges that come from volatile exchange rates.

- Reference(s)

-

- Ito, T., Koibuchi, S., Sato, K., & Shimizu, J. (2018). Managing currency risk. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lewis, L., & Morizono, Y. (2016). Japan's hidden treasure companies fear for their security. Financial Times, 12 January.

- Nguyen, T., & Sato, K. (2019). Firm predicted exchange rates and nonlinearities in pricing-to-market. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 53, 1-16.