| Author Name | YOUM Yoosik (Visiting Fellow, RIETI) / YAMAGUCHI Kazuo (Visiting Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

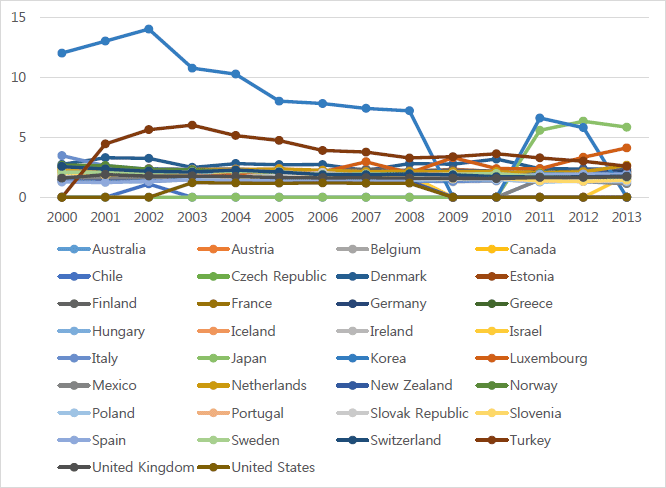

According to International Labor Office statistics from 2015, among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, Japan and Korea showed the highest gender inequalities in the proportion of managerial positions. Figure 1 reveal that Japan and Korea are easily distinctive among the OECD countries with the highest gender inequalities. In order to understand these abnormal gender inequalities, we need to decompose the disparity. The disparity may possibly be the result of a gap in human capital between genders. Depending on the sources of the disparity, the strategy for improving gender equality could be quite different. If human capital such as education and experience is the basis of the inequality, we need to launch policies to improve the accumulation of human capital in the form of women. However, if the source is not the human capital gap but rather is a glass ceiling, we want to examine and change the practices of promotion in firms.

Figure 1: Odds of Men vs. Women in Managerial Positions among OECD Countries

Sourece: Adapted from ILO 2015. Values not available data in specific years were coded as zero.

Yamaguchi (2014) analyzed the gender difference in the proportion of managers or supervisors in Japan by using the counter-factual decomposition method of DiNardo-Fortin-Lemieux (DFL). Table 1 summarizes the unexplained portion of gender inequality in Japan from the study that utilized a 2009 RIETI survey. Two interesting facts are revealed. First, as we add more human capital covariates, the unexplained portion shrinks, which indicates that a portion of gender inequality in managerial positions could be explained by gender inequality in human capital. But even after factoring in counter-factual treatment with age, education, and employment duration, the unexplained portion still remains at 70% to 80%. Second, as we move from kakaricho (task group head) position to kacho (section head) position, we still see about a 10% bigger unexplained portion. Although we could not examine the bucho (department head) position since there is an insufficient number of such females in the data, the current result implies a possible glass ceiling or pipe leaking even from the middle manager positions in Japanese firms among regular workers.

| Kacho | Kakaricho | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| difference | unexplained | explained | difference | unexplained | explained |

| -0.3 | 79.0 | 21.0 | -0.3 | 69.7 | 30.3 |

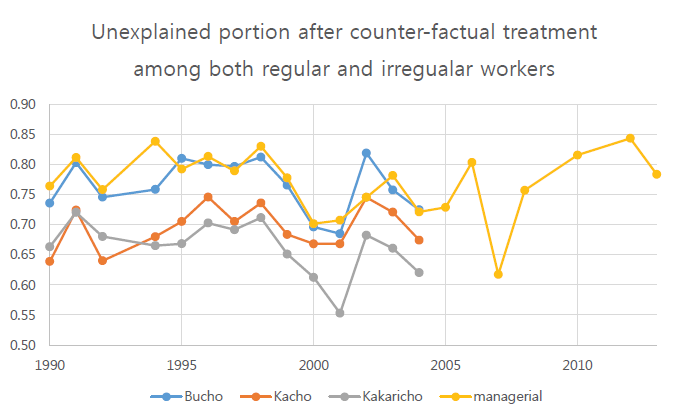

Figure 2 illustrates the trend of glass ceilings in Korea by using the same decomposition method. Three facts are revealed from the figure. First, for the unexplained portion after counter-factual treatment for human capital including age, duration of employment, educational level, and three interaction terms between each pair of human capital factors, the range of unexplained gender inequality for managerial positions lies between 75% to 85% except in 2007 when the portion was 62% (yellow line). This corresponds somewhat to that of Japan, which is 70% for kakaricho and 80% for kacho. Since Korean managerial positions include bucho and higher, the numbers seem strikingly similar. Second, as women move up to higher positions in the firm, from kakaricho (grey line) to kacho (orange line) to bucho (blue line), they face a higher unexplained portion just like Japanese women. This fits well with the glass ceiling picture although we do not have the data for the very high level managerial positions. It is also interesting that the unexplained portion was quite similar between kakaricho positions and kacho positions until 1997. There seems to be little improvement in gender equality with regard to promotion to managerial positions in firms over the last quarter century in Korea.

Figure 2. The Trend in the Glass Ceiling among Regular Workers in Korea from 1990 to 2013

- Reference(s)

-

- Yamaguchi, K. (2014). "Gender Difference in the Proportion of Managers/Supervisors among White-Collar Regular Workers in Japan." Presented at the symposium of the Asia Research Fund. Seoul.