In Japan, the COVID-19 crisis has subsided for the moment, but the situation remains precarious, with a new variant of the COVID-19 virus emerging and waves of infection resurging across the world.

Over the past two years, the global economy and society have continued to be shaken by COVID-19. In 2020, the global economy plunged into a more serious recession than the one that followed the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. In Japan, too, gross domestic product (GDP) recorded the largest fall since the end of World War II in the spring of 2000, when a state of emergency was declared for the first time in the country.

Under these circumstances, the problem of inequality, which has persisted as a matter of concern since the end of the 20th century, has come into the spotlight once again. That is because the recession has had a huge impact on non-regular workers and small and medium-sized service businesses. The government's economic measures have focused on supporting socially vulnerable people and small and medium-sized enterprises that are struggling financially.

♦ ♦ ♦

Apart from the immediate effects, the COVID-19 crisis is generating permanent economic and social effects. The Kishida administration has taken up the banner of "new capitalism." In this column, I will explore infectious diseases, capitalism, inequality and the government's role from historical perspectives.

The relationship between infectious diseases and mankind dates back to the prehistoric age. Japan has been struck by repeated epidemics of disease since ancient times. Infectious diseases occur in areas where people are concentrated, as indicated by the emphasis placed on the need to avoid the three Cs—closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings— amid the COVID-19 crisis. COVID-19 infections surged in metropolitan regions, such as Tokyo and Osaka.

For agriculture, which had provided the economic foundation over thousands of years before the modern era, the presence of large swaths of land was indispensable, and as a result, populations were inevitably dispersed spatially. However, in the 18th century, it was the manufacturing industry that led the modern capitalist economy, which emerged through the Industrial Revolution. In contrast with the case of agriculture, density is beneficial for the manufacturing industry, so populations became concentrated in cities. The history of the development of industrialized countries during the past two centuries is also a history of urbanization.

Since its inception, the capitalist economy has been growing even while being threatened by the inherent risk of infectious diseases. Naturally, the rise of the income level due to economic development has advanced human health through the improvement of living and dietary standards and the development of medical technology, but this progress has in no way been linear.

For example, the average life expectancy in Japan in 1900, when the novelist Natsume Soseki traveled to London as a student, was 43 years old, not very different from the average life expectancy in the United Kingdom at that time, which was 45 years old. On the other hand, per-capita income in Japan was around a quarter of the UK level, which was the highest in the world. The reason that the average life expectancy in Japan, where the income level was lower than in Chile and Mexico, was similar to the average in the United Kingdom, is that the Japanese industrial development at that time was still an ongoing process, with many Japanese people still engaging in agriculture in rural villages. In the United Kingdom, the advantages of high incomes were offset by the disadvantages of population concentration in urban areas where public health was underdeveloped.

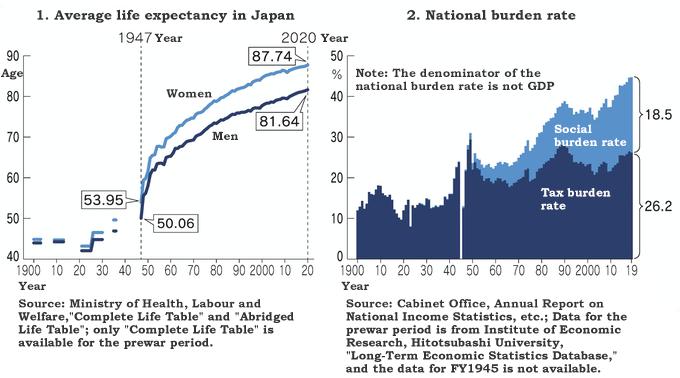

In Western industrialized countries in the first half of the 20th century, the average life expectancy increased steadily due to economic growth, development of public health, and the advance of medicine. However, in Japan in the prewar period, the average life expectancy had hardly increased (see Figure 1). At first, the Japanese government in the Meiji Period (1868-1912) promoted the development of basic public health services. However, after the beginning of the 20th century, the Japanese government became preoccupied with military buildup and neglected to develop water infrastructure and healthcare systems. In the prewar period, the "social burden," or social contributions to the financing of social security, was minimal. That is why the average life expectancy in Japan remained stagnant in the prewar period.

In 1947, in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the average life expectancy in Japan was 50 years old for men and 54 years old for women, the lowest figures among industrialized countries. However, the average life expectancy in Japan has now increased to 81.6 years old for men and 87.7 years old for women, among the highest in the world. The factors behind the increase in life expectancy in the postwar period include not only economic growth and the development of medical technology but also the improvement of the social security systems, such as pension and health insurance.

The development of capitalism that started in the 19th century also represented the history of a struggle with inequality. The inequality in capitalist society, which depended mainly on the manufacturing industry, was much larger than that which had been seen in traditional rural communities. It was in 1848 that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto, recognizing the widening of inequality as an irreparable systemic fallacy of capitalism and advocating a shift to socialism.

Against this historical background, Western industrialized countries created social security systems as a "bulwark against inequality" in the late 19th century through the 20th century. "Night-watchman states," in which the government focused on performing a minimal role in areas such as the judiciary and foreign policy, disappeared around 150 years ago. The economist Paul Samuelson gave the name "mixed economy" to the new economic system created in the 20th century, that is, a capitalist economy in which the government actively engages in income redistribution. That was the arrival of a "new capitalism."

However, the problem of inequality has not been resolved. In fact, the COVID-19 crisis has thrown this problem into sharp relief once again. The inequalities that we are now witnessing include those which have been temporarily amplified by the COVID-19 crisis and those which reflect historical trends that occur over a span of dozens of years. Although the COVID-19 crisis has currently captured our attention, the historical trends, including the aging of society coupled with a low birthrate, pose a more serious problem.

While longevity is something to be applauded, there is a much wider inequality in terms of income, assets, and health conditions among the elderly than among the working-age generations. The aging society is also an inequal society. One in five elderly people lives alone. Inequality is a not problem that can be resolved through self-help efforts alone.

♦ ♦ ♦

The Kishida administration aims to create a "virtuous circle of growth and distribution." The idea is that in the short term, giving people benefits will promote growth by inducing consumption. However, because of concerns over the future of social security, most of the benefits doled out will be used to build up savings, rather than to consume. The story is the same for the wage increase that the government requested of industry. Even if wages for a single year are raised, the impact on consumption will inevitably be limited unless families feel confident about a permanent income rise. Unless long-term problems are resolved, even a short-term "virtuous circle" is unlikely to emerge.

It is economic growth that drives a permanent income rise. Innovation is the wellspring of economic growth, particularly the kind of growth that boosts per-capita income. As John Maynard Keynes proclaimed that "animal spirits" are the driving forces that allow private enterprises to create innovation, the task for the government is to promptly execute a growth strategy instead of merely resorting to empty rhetoric, in order to realize economic growth via innovation.

Income redistribution intended to curb inequality is necessary for social stability. The fact that there has never been a prosperous country with a shrunken middle class is an important lesson of history. In Japan's case, resolving inequality is also the prerequisite for arresting population decline.

In a capitalist society, taxation and social security are the programs that curb inequality in the medium and long terms. It goes without saying that if social security systems, including pension, healthcare, and nursing care, are to be maintained, it is essential that society bears a commensurate burden. The tax burden in postwar Japan as a proportion of national income has mostly remained stable. However, the "social burden rate," which represents social insurance payments, has risen to 18.5% in recent years, after starting at zero (see Figure 2).

The national burden rate, which represents the total of tax and social security payments as a proportion of national income, is 44.7% in Japan. Among major European countries, the national burden rate is 48.6% for the United Kingdom, 55.8% for Germany, and 68.0% for France. On the other hand, the elderly ratio (the ratio of people aged 65 or older to the total population) is 29.1% in Japan, 22.0% in Germany, 21.1% in France, and 18.8% in the United Kingdom. Japan is the front-runner among those aging societies.

At the current national burden rate, it will be impossible to maintain the social security systems. Although public expenditure is barely supporting the systems, there is a chronic tax revenue shortfall, which in turn causes a chronic budget deficit. With the size of public debts being double the size of GDP, forming a societal consensus regarding the "burden" is the most important task that can only be accomplished by the government with regard to "distribution."

* Translated by RIETI.

January 4, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun