Toyota Motor is cooperating with Uber Technologies, a U.S. car-dispatching-service company, in the development of self-driving technology. Meanwhile, many U.S. companies have opened call centers in the Philippines. Companies are not only connected with each other globally, across the boundaries of developed countries, emerging countries and developing countries, through supply chains for materials and parts but also connected through business partnerships and outsourcing concerning various business operations, including design, research, development, marketing and after-sale service.

Those networks of companies are called global value chains (GVCs).

The expansion of GVCs is making significant contributions to the development of the global economy. One reason for this development is that companies can allocate resources, including workers and capital, more efficiently by using GVCs. In the case of Japanese companies, it is possible to earn more profits by offshoring simple manufacturing processes to developing countries while focusing on manufacturing processes requiring higher skills as well as research and development in Japan.

A more fundamental reason is that technology and knowledge spread worldwide through GVCs. Connecting with business partners, including foreign ones, enables companies to create innovations by acquiring new technology and knowledge that they would find difficult to acquire on their own. Prominent examples of these patterns include the development and transfer of technology under supplier-customer relationships regarding parts and materials and open innovation through joint research. As Professor Paul Romer of New York University, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2018, points out, innovations achieved through knowledge diffusion are the ultimate source of economic growth.

♦ ♦ ♦

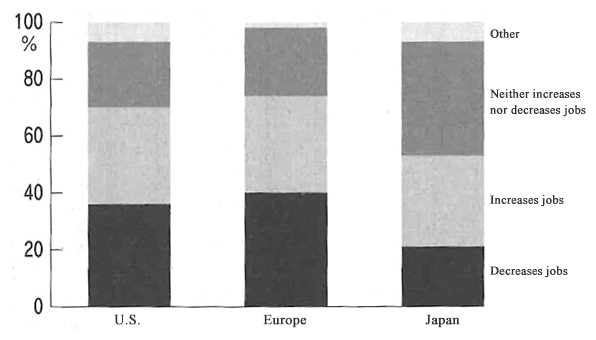

However, in recent years, skepticism about economic globalization, including the expansion of GVCs, has been growing worldwide. According to one opinion survey, the proportion of the population who expect international trade to increase jobs is only around 30 to 40% in the United States and Europe and only 20% in Japan (See the figure below).

As a result, we have witnessed various protectionist moves, including the United States' decision not to participate in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the United Kingdom's decision to exit the European Union, and the U.S.-China trade friction. Since the global financial crisis of 2008, international trade and investment have remained stagnant.

There are three major reasons for the rise of protectionism.

The first reason is that the expansion of GVCs, while bringing overall economic growth, has generated income inequality within developed countries due to the competition with emerging countries. For example, Professor Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other researchers empirically showed that production and jobs in the United States are decreasing due to imports of Chinese products. People in regions that depend mainly on traditional manufacturing industries such as the Midwest U.S., where the impact has been particularly severe, are the strongest supporters of protectionism.

The second reason is that because of cross-border interconnectedness between companies, economic shocks that occur abroad affect domestic economies. The global financial crisis, which started in the United States, triggered a global recession. As adverse effects like this are easily visible, negative views on cross-border interconnectedness arise.

The third reason is that domestic technologies spill over to other countries through GVCs. The United States is accusing China of stealing advanced technologies. In developed countries, there have been strong negative reactions to the significant advances that emerging countries are making thanks to these spillovers of technologies from the developed world.

♦ ♦ ♦

However, the adverse effects of GVCs can be dealt with effectively.

First, it is possible to prevent developed countries' manufacturing industries from declining because of competition with emerging countries by changing their domestic industrial structures.

An analysis conducted by Michal Fabinger, a researcher at the University of Tokyo, showed that sales by domestic industries in Japan have increased due to imports from China. That is because unlike their U.S. counterparts, Japanese manufacturing industries export high-quality parts to China and import final goods assembled in China using Japanese parts. In the United States, the negative impact of imports from China has been small in Silicon Valley because the region's information technology industry develops hardware and software products and new services while outsourcing their production to emerging countries.

In other words, developed countries can co-exist with emerging countries and continue to prosper by changing the industrial structures in ways that create higher value added. For this purpose, developed-country companies should make more active use of GVCs without fearing globalization. For example, one way to do so is creating innovation by incorporating new information through the acquisition of foreign companies that possess cutting-edge technology and participation in international research collaboration.

It is also possible to deal with the effects of overseas economic shocks transmitted through GVCs.

According to an analysis that I conducted jointly with Yuzuka Kashiwagi at Waseda University and other researchers, the impact of hurricanes that struck industrial clusters on the U.S. East Coast affected companies in other U.S. regions through supply chains. However, the impact did not affect companies outside the United States or U.S. companies doing business with foreign countries despite being linked with companies damaged by the hurricane through supply chains. This is because it is relatively easy for companies connected with diverse international networks to find alternative business partners even if their existing partners are affected by natural disasters.

Another study that I conducted showed that although the damage caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake extended beyond the disaster areas through supply chains, companies with diverse ranges of business partners achieved recovery relatively quickly.

That means, paradoxically, that the contagion of negative effects through networks can be mitigated by diversifying networks globally and by flexibly changing partners in accordance with current circumstances.

Finally, it is somewhat difficult to deal with the leakage of technologies through GVCs. That is because, fundamentally, the GVC is a channel of technology diffusion, as was mentioned earlier.

However, as the theft of technologies in the form of infringement on intellectual property rights stifles innovation, it has negative effects on the entire global economy. Therefore, it is necessary to make sure that emerging countries fully protect intellectual property by revitalizing the World Trade Organization (WTO) and expanding multilateral free trade agreements (FTAs), such as TPP11. In order to expand diverse networks, international rules are required to a certain extent.

♦ ♦ ♦

However, another reason for the growing skepticism about globalization and protectionism may be unrelated to economic benefits.

Many Japanese people who have negative sentiment about international trade are no doubt receiving the benefits of trade. They support protectionism regardless of the economic benefits they receive from globalization presumably because of the intrinsically closed nature of human beings. During the evolution process, human beings came to form small groups, with strong bonds forged within each group, and the groups competed with each other for survival. That is why human beings cannot be generous with outsiders, according to Robin Dunbar, an evolutionary biologist.

Therefore, in order to counter protectionism, it is necessary to mitigate the intrinsically closed nature of humans. That can be done through social experience and education. According to an analysis by Professor Eiji Yamamoto of Seinan Gakuin University and others, people who have the experience of playing group sports are more likely to place emphasis on teamwork, trust other people and support free trade than people who do not. People realize the importance of diversity and the defects of closedness by mingling and competing with many other people under a framework of common rules. Such diverse ties between workers were found to produce higher incomes, according to a study by Professor Ronald Burt of the University of Chicago.

However, it is not easy either for companies or for individuals to develop diverse networks globally, because of the associated costs. Therefore, while it is naturally necessary for companies and individuals to make efforts to accomplish this, governmental support is essential. It is desirable for the government to provide "networking support"—support that enables individuals and various economic agents to interact and interconnect with each other and extend their networks abroad— including support for companies' business platforms and for overseas education for students.

Historically, the intrinsically closed nature of humans generated protectionism, as attested by the rise of the sonno joi (revere the emperor and expel foreigners) movement around the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the emergence of the bloc economies before World War II, and the results were sometimes devastating. However, human beings have surmounted those crises and have restored, developed and maintained diverse networks. I hope that the rise of protectionism in recent years will be overcome quickly by human wisdom and appropriate policies.

* Translated by RIETI.

February 5, 2019 Nihon Keizai Shimbun