Come March, it will be five years since the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station of Tokyo Electric Power Company, Inc. (TEPCO). The incident made it a national imperative to carry out a complete overhaul of the government's energy policy. Are we making real headway in this endeavor? To put the conclusion first, the situation is unsettled as the pace of progress varies greatly across different segments of the energy sector. Overall, we have more unfinished work than finished, with no tangible progress made in the area of nuclear power policy reform.

Among various areas of the ongoing energy reform, the reform of electricity and gas systems has made relatively good progress. With regard to the electricity system reform, the Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators (OCCTO) was established in April 2015, and the electricity retail market will be fully liberalized in April 2016. Furthermore, the vertical separation of electricity transmission and distribution operations from generation and other operations of electric power companies will be implemented in 2020 in the form of legal unbundling. As to the gas system reform, the retail market will be fully liberalized in 2017, followed by the legal unbundling of gas distribution pipeline operations from other operations of Japan's three major gas companies—Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd., Osaka Gas Co., Ltd., and Toho Gas Co., Ltd.—in 2022.

The implementation of these system reform steps will enable all users, including households, to choose their electricity and gas suppliers. Full-fledged competition in the liberalized market will improve the governance of major electricity and gas companies, which tends to be rather lax due partly to the rate-of-return pricing system maintained in the core segment of their business.

♦ ♦ ♦

In stark contrast, nearly five years since the Fukushima incident, little progress has been made in the much-needed reform of nuclear power policy and programs. In April 2014, the Cabinet adopted a new Strategic Energy Plan for the first time since the March 2011 disaster. In its introductory section, the plan states as follows: "We will do our utmost to achieve the reconstruction and recovery of Fukushima... Japan will review from scratch the energy strategy that it mapped out before the Great East Japan Earthquake. Japan will minimize its dependence on nuclear power. Needless to say, that is the starting point for rebuilding Japan's energy policy."

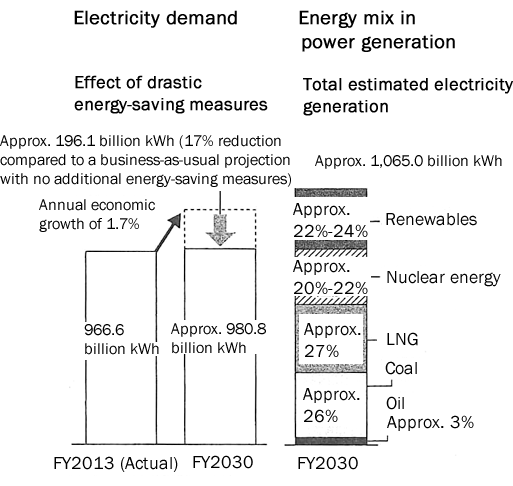

In line with this, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has repeatedly pledged to "reduce dependence on nuclear power generation as much as possible." But this promise has never been fulfilled. As shown in the figure below, in its energy mix outlook determined in July 2015, the government revealed its plan for nuclear energy to account for 20% to 22% of electricity generated in FY2030. The reason why this is amounting to a "breach of promise" is as follows:

The Act on the Regulation of Nuclear Source Material, Nuclear Fuel Material and Reactors (hereinafter "Nuclear Reactor Regulation Act") as amended in 2012 provides that nuclear power reactors shall be decommissioned, in principle, upon reaching 40 years in service. However, as an exception to the principle available only when special conditions are met, the operational life of reactors may be extended by 20 years just once, enabling certain reactors to operate for a maximum of 60 years. Only 18 of the existing 43 nuclear power reactors in Japan will have been in service for less than 40 years at the end of December 2030, meaning that 25 reactors will be decommissioned by then if the 40-year rule is applied strictly.

Adding two reactors currently under construction—Chugoku Electric Power Co., Inc.'s Shimane No. 3 reactor in Shimane prefecture and J-Power's Oma reactor in Aomori prefecture—to the remaining 18 would make only 20. Assuming that these 20 reactors would be operating at 70% of their capacities, nuclear power would account for approximately 15% of total estimated electricity generation of 1,065.0 billion kWh in FY2030.

Thus, if the 40-year rule proves to be effective, Japan's dependence on nuclear power in FY2030 would be around 15%. The government's target of 20% to 22%, which exceeds the estimate by five to seven percentage points, must have been premised on the extension of the operational life of existing reactors or the construction of additional new reactors. Since the Cabinet of Prime Minister Abe maintains that the construction of any new or additional reactor is not assumed at the moment, the extra five to seven percentage points would have to come solely from continuing to operate existing reactors beyond their 40-year limit, namely, the extension of the operational life of reactors.

Of the 25 reactors that would be decommissioned by 2030 based on the strict application of the 40-year rule, included are the four reactors at TEPCO's Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Station. Many (15 or so) of the 21 reactors that remain after excluding the four from Fukushima Daini would have to be kept in service beyond 40 years in order to achieve the additional five to seven percentage points.

In other words, the exceptional rule of 60 years of service, instead of the basic rule of 40 years of service, under the Nuclear Reactor Regulation Act would become the normality. Such a far-fetched interpretation of the law is not consistent with Prime Minister Abe's pledge to "reduce dependence on nuclear power generation as much as possible."

♦ ♦ ♦

Regardless of the level of dependence, if we are to continue to use nuclear power at any rate in the future, it is an essential prerequisite to make every possible effort to minimize the risks involved. How can we minimize the risks associated with nuclear power generation? Needless to say, using state-of-the-art facilities is the answer.

However, the existing nuclear power facilities in Japan are far from that state. Roughly half (22) of the existing reactors are boiling water reactors (BWRs) and four of them are advanced boiling water reactors (ABWRs), which is the present state-of-the-art type. However, the remaining half (21) are all conventional pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and there is not a single state-of-the-art advanced pressurized water reactor or AP1000 PWR developed by Westinghouse Electric Company LLC. In contrast, AP1000 reactors will reportedly begin operation soon in China.

If nuclear power is to remain a source of energy in Japan, the government should seek to replace aging reactors with state-of-the-art reactors within the same nuclear power plant premises, which is what a responsible government is supposed to be doing. In reality, however, the government has been avoiding a straightforward discussion on the need of such replacement, resorting to the extension of the operational life of reactors, a makeshift measure. I cannot help but to call it an "irresponsible return to the pro-nuclear power policy."

Of course, simply emphasizing the need to replace aging reactors with advanced ones would not sit well with public opinion favoring the minimization of dependence on nuclear power or the Abe Cabinet's public commitment to achieving that end. Even in the case of promoting the replacement of aging reactors, Japan should reduce its dependence on nuclear power to around 15% in 2030. Replacing aging reactors with advanced reactors within the framework of keeping the dependence on nuclear power to the lowest possible level is about the only responsible way to go, if Japan is to continue to use nuclear power energy in the future.

The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station illuminated the need for energy policy reform, and the government has been making vigorous efforts to reform the electricity and gas systems. Why then does the government remain so hesitant to take bold steps to reform its nuclear energy policy? The answer is that, while reforming the electricity and gas systems would win votes for politicians, reforming nuclear energy policy would not (or could reduce votes).

♦ ♦ ♦

The lack of a long-term perspective in the government's energy policy is not limited to the area of nuclear energy.

In determining the energy mix in 2030, the government maintained that the share of renewable energy sources should be held down because the cost of feed-in-tariffs (FITs) would increase electricity prices. Suppressing the use of renewable energy sources because of the problem with the FIT system is tantamount to throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

To begin with, a padding scheme like FITs will not be sustainable. Given that, and considering the importance of renewable energy sources, a serious policy debate should have taken place on how Japan would be able to introduce them on a market basis in determining the energy mix. In reality, however, policymakers were preoccupied with the challenge right in front of them, namely, the review of the FIT system.

How to win the next election is at the top of the minds of politicians, whereas the greatest concern for bureaucrats is what position they will be assigned to next. Therefore, both politicians and bureaucrats are inclined to focus on issues in the next two to three years so that they can earn credits for their respective next steps. This inhibits the development of an appropriate energy policy package, for which a long-term perspective of 20 to 30 years from now is indispensable. This year marks the fifth year since the devastating nuclear incident. We must take this opportunity to break the ongoing impasse by mobilizing the power of the private sector including private-sector companies and local residents.

* Translated by RIETI.

January 19, 2016 Nihon Keizai Shimbun