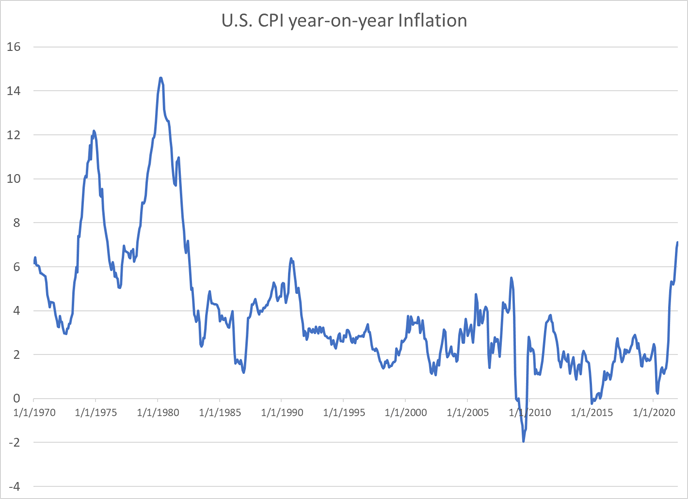

The biggest challenge facing the U.S. economy is high inflation. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of December 2021, U.S. consumer prices grew by 7.1% year-on-year, the highest pace since June 1982. Even based on the CPI that excludes food and energy (whose prices tend to be volatile), the inflation rate was 5.5%, the greatest rate increase since 1991.

High inflation in the U.S. is more of a recent phenomenon. Before the pandemic, the rate of inflation was relatively constant at somewhere around 1.5% to less than 2%. In the beginning of 2021, the rate of inflation was still not that high, until it started accelerating in May and stayed at a level comparable to 1982 (Figure 1).

The prices of goods and services rose in a wide range of items and categories. Compared to December 2020, the price of renting a car went up by 36%. The price of furniture rose by 17%, men's coats and suites by 11%, food prices by 6.3%, on and on.

Why is inflation at a 40-year high?

From a macroeconomic perspective, inflation can happen when the demand for goods and services is greater than their supply. Insufficient supply helps raise the price level. More concretely, if many people want to buy a piece of furniture, say a sofa, but if there are not enough sofas available for everyone, some people may be willing to buy a sofa even if the price is higher than usual. The price level of things can rise if the demand for goods and services are not being met by the supply.

Why are we experiencing such high inflation now? That is because the gap between the demand and the supply is particularly large, mainly due to disruptions in the supply side of the economy caused by the pandemic.

The demand for goods and services is robust because the U.S. economy is recovering from the lowest point that it reached in 2020. Especially before the vaccine became available in the beginning of 2021, people had to postpone shopping, vacationing, and other economic and business activities. Once vaccination started becoming available, people started feeling more comfortable about being outside and interacting with people, and consequently, the economy started functioning more normally compared to 2020, leading people to demand more goods and services. The government that was afraid of its economy free falling into a new Great Depression, also tried to boost people's purchasing power through massive fiscal stimulus as exemplified by the $1,400 stimulus checks it provided. The Federal Reserve Board joined the efforts to stimulate the economy by lowering the policy interest rate to zero and implementing the quantitative easing (QE) policy (a central bank's policy to buy financial assets such as government bonds with freshly printed money).

While the demand side of the economy has been extremely active, the supply side of the economy has been disrupted.

Labor shortage is the biggest problem in the supply side of the U.S. economy. It has disrupted supply chains, because factories, ports, trucking companies, and warehouses in the U.S. cannot hire enough people to operate at full capacity. Across the country, production and shipments tend to be delayed, and shelves are empty or near-empty at supermarkets and stores. Many cargo ships are forced to wait to enter major ports such as Los Angeles and New York. Ports do not get cleared because of the shortage of unloading staff or truck drivers. Even if products manage to get to stores, there are not enough people to stock the shelves.

The service sector has been severely impacted by a labor shortage as well. While it has been damaged from the beginning of the pandemic, recently, the situation with the labor shortage is getting worse. Medical and hospitality industries such as hospitals, hotels, and restaurants cannot hire enough people for their operations, because some people fear becoming exposed to COVID-19 at the workplace. Or, simply, some people cannot go to work because of infection with the new, highly transmissive Omicron variant. Many schools are closed due to not just students becoming ill but shortages of teachers and staff.

Thus, while there is a strong demand for goods and services, the economy cannot meet the demand. That increases the prices of goods and services. The more severe the supply situation is, the more pressure on the prices to rise. That means until the disruptions in the supply chains and the labor shortage are solved, the current situation with high inflation will necessarily continue.

What impact does inflation have?

High inflation can erode people's purchasing power, unless their wages also rise proportionally. In the current environment, workers can afford to seek higher wages because the labor shortage strengthens their bargaining power. Such workers are even prepared to voluntarily leave their work because they know the demand for labor is so strong that finding a job is relatively easy, and workers also think that they can wait for wages to continue to rise. The U.S. economy is facing the situation known as "The Great Resignation," a term coined by Anthony Klotz (Professor at Texas A&M University), referring to a record high number of people leaving their jobs voluntarily. In this way, higher prices will lead to higher wages.

Companies that decide to hire workers with higher wages try to pass their losses into the prices of their products and services. Hence, people foresee higher prices in the future and demand even higher wages to maintain their purchasing power. Higher wages can thus help raise price levels. Such a wage-price spiral could be the worst that the U.S. economy (or any economy that experiences a rapid rise in prices and wages) can experience. The last time the U.S. economy experienced a wage-price spiral due to a negative supply shock (i.e., the oil shocks in the 1970s), it led to very high inflation (the CPI inflation was over 14% in 1980).

Some economists argue that the U.S. economy will not experience a severe wage-price spiral like what happened in the 1970s, for two reasons. First, the U.S. economy is not as unionized as it used to be. The rate of private union membership in 2020 was merely 6.3% of the working population, a big drop from 24.2% in 1973 (the public-sector union membership rate is 34.8%, which represents a moderate declining from 38% in the 1980s). This means that workers' bargaining power may not be as strong, making it harder for wages to rise.

Second, globalization has intensified price competition among firms around the world, meaning that firms continue to face downward pressure in the prices of their goods and services. Hence, firms may find it harder to pass higher wages through to higher prices. Thus, upward pressure in wages may not lead to higher prices in the globalized world we live in.

Nonetheless, some industries and companies are experiencing a unionization movement (e.g., Starbucks). Also, as The Economist magazine points out, since the late 2010s, the world seems to be experiencing de-globalization, because some countries have pursued populist, protectionist policy (e.g., Trump's America), and the 2020 COVID crisis damaged or fragmented supply chains so much that offshoring has reversed (i.e., onshoring). Some companies and industries have started relying more on domestic production bases despite the higher costs. Thus, if unionization and de-globalization rise, it may help high inflation to persist.

What can or should be done to lower inflation?

To contain the inflationary pressure, the Fed has started tightening monetary policy. In November 2021, the Fed first started tapering the QE policy. It is expected that while the Fed continues to taper QE, it will also start raising the short-term policy rate. As of this writing, the Fed has mentioned that it will raise the rate three times in 2022. Both the end of zero-interest-rate and QE policies are aimed at increasing the cost of borrowing from banks, and thereby, making it more expensive for banks and firms to consume and make investments. In principle, once contractionary monetary policy cools down the economy, inflation should be subdued.

However, this kind of policy entails the risk of causing a recession. In the beginning of the 1980s, to stop high inflation, Paul Volker, then Chairman of the Fed, raised the policy interest rate significantly (to 20%!), but that caused a severe recession (with the U.S. GDP growth rate becoming -1.8%, the biggest contraction since the 1930s). It was so severe that people thought the U.S. would experience another great depression. Hence, implementing contractionary policy must be undertaken cautiously.

To avoid such an outcome, it is important for the Fed to implement contractionary policy gradually while maintaining smooth communication with market participants. The last thing the Fed wants to do is to surprise the markets with unexpected policy or actions. Surprise among market participants would only increase the level of uncertainty about the future. Uncertainty and the increased risk that such uncertainty poses to businesses can make it harder for firms and banks to make investments.

Another issue the Fed needs to be cautious about is the impact of U.S. monetary contraction on emerging market economies.

Many of these economies are indebted to foreign investors, and about 60% of the debt is denominated in the U.S. dollar. Once the Fed implements contractionary monetary policy, U.S. interest rates could rise, increasing the demand for U.S. dollar-denominated assets, helping the currency appreciate. Dollar appreciation would increase the debt burden for dollar-indebted economies. Many emerging market economies are already beset with rising debt because the pandemic-induced economic crisis has increased fiscal expenditures and decreased tax revenues, widening fiscal deficits.

Hence, a rise in the debt burden due to dollar appreciation could make it difficult for emerging market economies to manage their economies. There is a precedent. A mere mention of monetary contraction by then Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke in May 2013 led to a rapid rise in the 10-year U.S. Treasuries, a sharp dollar appreciation, and rapid depreciation among the currencies of several emerging-market economies that were highly indebted in the dollar – this came to be known as the "Taper Tantrum."

This is a good example of how an unpredictable policy change by the U.S. could send jitters through global financial markets and hurt developing economies. Higher predictability of US monetary policy, achieved through good communications with markets and other authorities, is highly desirable and good for not just emerging market economies but also the U.S. itself.