Introduction

Ahead of the G20 summit in Osaka from June 28 to 29, 2019, the T20 (Think 20) summit was held in Tokyo from May 26 to 27. The T-20, which serves as an "idea bank" for the G20, is one of the G20 formal engagement groups (organizations established on an agenda-by-agenda basis and a function-by-function basis which are independent from governments) that are comprised of think tank experts and other knowledgeable people from G20 and other countries. The T-20 established task forces and held discussions on 10 policy challenges related to major themes of the G20 Osaka summit and issued a joint statement that summarized the policy proposals from the task forces at the T20 summit.

Of the 10 task forces, the Task Force on Trade, Investment, and Globalization, comprised of think tank experts from around the world, held discussions mainly on the following three challenges: (1) reform of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and resolution of trade disputes, (2) the flow of digital data, and (3) initiatives to achieve sustainable and inclusive economic growth (services trade, global value chains (GVC), investment facilitation, etc.).

Of those themes, this paper examines the status of the policy debate on data flows. While national governments are already implementing various economic policies related to data flows in the real world, there is not yet a consensus among economists on how to approach data flows in the study of economics. There is also confusion in the debate over how policies related to data flows should be assessed. Therefore, as part of its policy proposal, the T20 put forward a framework of policy debate on data flows that is desirable from the perspective of economics. This framework will be explained below, but readers should keep in mind that there is not a full consensus on this framework among economists around the world.

1. Mishmash of Policy Approaches to Digital Economy

From the perspective of economists, the ongoing policy debate on data flows and other matters related to digital economy is in a state of great confusion. For example, if privacy is to be rigorously protected as a human right as is argued in Europe, regulation may become more and more strict, undermining economic efficiency. Meanwhile, when it comes to the matter of national security, as in the case of the debate on cybersecurity, the policy debate goes nowhere beyond the preservation of security, with the issue of social welfare excluded from consideration.

In some cases, a digital economy-related policy involves multiple policy objectives. For example, with respect to governments' policies toward GAFA (Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon), there is a ragbag of policy objectives, including protection of people's privacy, competition regulation, cracking down on tax evasion, and protection of domestic companies. In the debate over the restrictions imposed on Huawei, no clear distinction has been made between two different policy objectives--cybersecurity and protection of domestic companies (industrial policy). Given the mishmash of policy approaches, including those that may be justified from the viewpoint of economics and those with hidden favoritism for domestic companies, we are now facing a dangerous situation.

The United States, the European Union and China, among other countries including India, are developing different policy regimes concerning data flows based on different logical frameworks. How to ensure policy coordination between those different regimes is also a challenge.

2. Establishment of Data Flow Policy as Economic Policy

Here, we reflect on the relationship and similarity of data flows with trade in goods and services.

First, it is necessary to provide a fair assessment of the contributions of data flows to the economy. In the study of economics, it is assumed that free trade increases social welfare for the whole economy. The convenience and efficiency that consumers and users can enjoy should be the ultimate benchmarks for assessment. From that viewpoint, the idea that free flows of data contribute positively to the economy serves as a theoretical starting point.

This applies not only to developed countries but also to emerging and developing countries. Digital technology can be divided into the IT field (information technology field), which includes artificial intelligence and robotics, and the CT field (communication technology field), which includes the internet and smartphones (5G). Most emerging and developing countries may be no match for developed countries at the cutting edge of IT. On the other hand, in the case of CT, even in developing countries, smartphones have become popular not only in metropolitan areas but also in rural areas. People in developing countries are making successful use of CT in their everyday lives and economic activities. In that sense, it is necessary for G20 and other countries around the world, especially emerging and developing countries, to develop policies for using data flows for the sake of economic growth.

Free access to information provided by the internet is convenient, as you may know from your own experience, but it is also accompanied by economic problems and social concerns. It is essential to identify those problems and concerns, systematically classify relevant policies with due consideration for economic efficiency, and clarify points of discussion. In addition, policies concerning the flow of data itself (e.g., regulation) and policies concerning data-related businesses (e.g., industrial promotion and regulation) cannot be separated from one another. In the debate on data flows, how domestic and international policies should be linked and coordinated is also important, as in the case of services trade.

3. Proposal from T20: Develop a Policy Regime Based on Free Data Flow

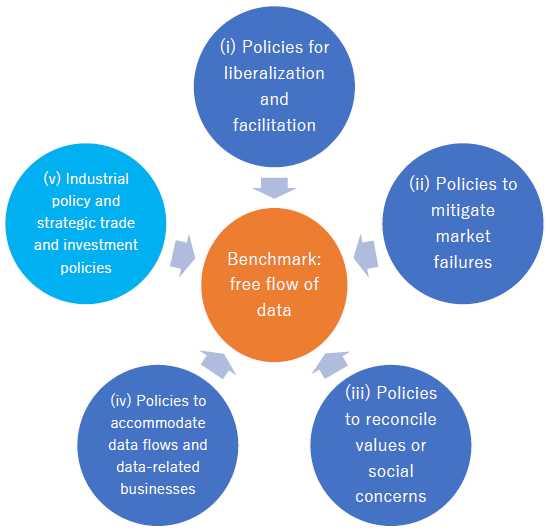

Based on the ideas in the previous section, the T-20 proposed that policies should be classified into the following five categories based on "free flow of data."

The first category of policy promotes further liberalization and facilitation of data flows and removal of obstacles to free flow of data. Policy concerns in this category include the principle of non-discrimination for digital content, maintenance of the practice of not imposing tariffs on e-commerce (the WTO has not yet made a decision on this matter), exemption of small parcels from tariffs, and the use of electronic authentication and signature.

The second category of policy mitigates economic concerns (market failure). Among policy concerns in this category are competition policy (e.g., prohibition of abuse of dominant market power and prohibition of unfair trade), protection of consumers, and protection of intellectual property rights, for example.

The third category of policy reconciles values and social concerns with economic efficiency. Policy concerns in this category include protection of data and privacy, cybersecurity, and other general exceptions (e.g., health and culture).

The fourth category of policy incorporates data flows and data-related businesses into the regulatory regime. Policy concerns in this category include taxation, electronic payment, fintech, other industrial regulations, artificial intelligence, corporate information disclosure and statistics, and due process (criminal law procedures) in government access to privacy/industry data.

Finally, the fifth category of policy promotes industrial development and protects infant industries (this category of policy is protectionist in some cases). Although it is appropriate to grow domestic industries, it is a matter for discussion to what degree protection should be allowed. In order to prevent excessive protection, standards should be set under the WTO, for example.

The classification of data flow policy into the above five categories enables us to discuss the appropriateness of policy from the viewpoint of economics. As a result, it becomes possible to achieve policy harmonization in some policy areas and to identify areas where policy harmonization cannot be easily achieved.

4. Significance of "Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT)"

It is very significant that "data free flow with trust (DFFT)" was mentioned in the leaders' declaration (communique) and an agreement was reached on the launch of the "Osaka Track," a framework for promoting DFFT, at the G20 Osaka summit. At present, as the United States, Europe, China and India are each developing different policy regimes based on different philosophies, the digital world is becoming more and more fragmented—in other words, digital protectionism is growing and a shift to a digital bloc economy system is proceeding, so to speak. In that sense, it is a big step forward that the G20 leaders agreed on a conceptual framework that can serve as a logical foundation at the Osaka summit. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was put into effect in December last year, incorporates a similar approach, but the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), which was put into effect in February this year, and the EU General Data Protection Regulation, which was enacted in 2016, have adopted entirely different approaches. Under the agreement reached on DFFT at the Osaka summit, it will become possible to distinguish between policy areas where international harmonization is easy to achieve and areas where it will be difficult to do so. It will also become possible to more strictly define the meaning of "rules" as referred to in the principle of "maintaining the international economic system based on rules." I hope that through debate on matters like this, inefficient industrial policy and protectionist policies will be identified and gradually corrected.

In any case, matters related to data flow policy cannot be resolved through debate at the WTO alone. Japan should promote further discussion and debate using various forums, including the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), while supporting debate at the WTO as the leader of the Osaka Track.